4.4. Minor Keys and Scales*

Each major key uses a different set of notes (its major scale). In each major scale, however, the notes are arranged in the same major scale pattern and build the same types of chords that have the same relationships with each other. (See Beginning Harmonic Analysis for more on this.) So music that is in, for example, C major, will not sound significantly different from music that is in, say, D major. But music that is in D minor will have a different quality, because the notes in the minor scale follow a different pattern and so have different relationships with each other. Music in minor keys has a different sound and emotional feel, and develops differently harmonically. So you can't, for example, transpose a piece from C major to D minor (or even to C minor) without changing it a great deal. Music that is in a minor key is sometimes described as sounding more solemn, sad, mysterious, or ominous than music that is in a major key. To hear some simple examples in both major and minor keys, see Major Keys and Scales.

Minor scales sound different from major scales because they are based on a different pattern of intervals. Just as it did in major scales, starting the minor scale pattern on a different note will give you a different key signature, a different set of sharps or flats. The scale that is created by playing all the notes in a minor key signature is a natural minor scale. To create a natural minor scale, start on the tonic note and go up the scale using the interval pattern: whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step.

Figure 4.22. Natural Minor Scale Intervals

Listen to these minor scales.

Exercise 4.4.1. (Go to Solution)

For each note below, write a natural minor scale, one octave, ascending (going up) beginning on that note.

Figure 4.23.

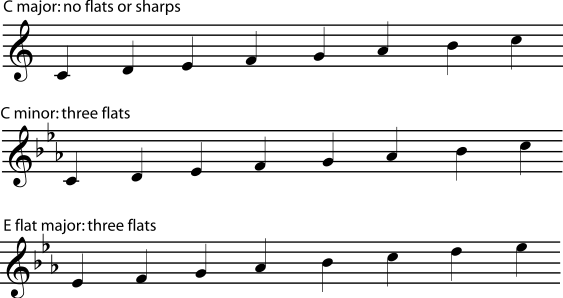

Each minor key shares a key signature with a major key. A minor key is called the relative minor of the major key that has the same key signature. Even though they have the same key signature, a minor key and its relative major sound very different. They have different tonal centers, and each will feature melodies, harmonies, and chord progressions built around their (different) tonal centers. In fact, certain strategic accidentals are very useful in helping establish a strong tonal center in a minor key. These useful accidentals are featured in the melodic minor and harmonic minor scales.

Figure 4.24. Comparing Major and Minor Scale Patterns

It is easy to predict where the relative minor of a major key can be found. Notice that the pattern for minor scales overlaps the pattern for major scales. In other words, they are the same pattern starting in a different place. (If the patterns were very different, minor key signatures would not be the same as major key signatures.) The pattern for the minor scale starts a half step plus a whole step lower than the major scale pattern, so a relative minor is always three half steps lower than its relative major. For example, C minor has the same key signature as E flat major, since E flat is a minor third higher than C.

Figure 4.25. Relative Minor

Do key signatures make music more complicated than it needs to be? Is there an easier way? Join the discussion at Opening Measures.

All of the scales above are natural minor scales. They contain only the notes in the minor key signature. There are two other kinds of minor scales that are commonly used, both of which include notes that are not in the key signature. The harmonic minor scaleraises the seventh note of the scale by one half step, whether you are going up or down the scale. Harmonies in minor keys often use this raised seventh tone in order to make the music feel more strongly centered on the tonic. (Please see Beginning Harmonic Analysis for more about this.) In the melodic minor scale, the sixth and seventh notes of the scale are each raised by one half step when going up the scale, but return to the natural minor when going down the scale. Melodies in minor keys often use this particular pattern of accidentals, so instrumentalists find it useful to practice melodic minor scales.

Figure 4.26. Comparing Types of Minor Scales

Listen to the differences between the natural minor, harmonic minor, and melodic minor scales.

Exercise 4.4.3. (Go to Solution)

Rewrite each scale from Figure 4.23 as an ascending harmonic minor scale.

Exercise 4.4.4. (Go to Solution)

Rewrite each scale from Figure 4.23 as an ascending and descending melodic minor scale.

Major and minor scales are traditionally the basis for Western Music, but jazz theory also recognizes other scales, based on the medieval church modes, which are very useful for improvisation. One of the most useful of these is the scale based on the dorian mode, which is often called the dorian minor, since it has a basically minor sound. Like any minor scale, dorian minor may start on any note, but like dorian mode, it is often illustrated as natural notes beginning on d.

Figure 4.27. Dorian Minor

Comparing this scale to the natural minor scale makes it easy to see why the dorian mode sounds minor; only one note is different.

Figure 4.28. Comparing Dorian and Natural Minors

You may find it helpful to notice that the "relative major" of the Dorian begins one whole step lower. (So, for example, D Dorian has the same key signature as C major.) In fact, the reason that Dorian is so useful in jazz is that it is the scale used for improvising while a ii chord is being played (for example, while a d minor chord is played in the key of C major), a chord which is very common in jazz. (See Beginning Harmonic Analysis for more about how chords are classified within a key.) The student who is interested in modal jazz will eventually become acquainted with all of the modal scales. Each of these is named for the medieval church mode which has the same interval pattern, and each can be used with a different chord within the key. Dorian is included here only to explain the common jazz reference to the "dorian minor" and to give notice to students that the jazz approach to scales can be quite different from the traditional classical approach.

Figure 4.29. Comparison of Dorian and Minor Scales

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 4.4.2. (Return to Exercise)

-

A minor: C major

-

G minor: B flat major

-

B flat minor: D flat major

-

E minor: G major

-

F minor: A flat major

-

F sharp minor: A major