1.1. Pitch

The Staff*

People were talking long before they invented writing. People were also making music long before anyone wrote any music down. Some musicians still play "by ear" (without written music), and some music traditions rely more on improvisation and/or "by ear" learning. But written music is very useful, for many of the same reasons that written words are useful. Music is easier to study and share if it is written down. Western music specializes in long, complex pieces for large groups of musicians singing or playing parts exactly as a composer intended. Without written music, this would be too difficult. Many different types of music notation have been invented, and some, such as tablature, are still in use. By far the most widespread way to write music, however, is on a staff. In fact, this type of written music is so ubiquitous that it is called common notation.

The Staff

The staff (plural staves) is written as five horizontal parallel lines. Most of the notes of the music are placed on one of these lines or in a space in between lines. Extra ledger lines may be added to show a note that is too high or too low to be on the staff. Vertical bar lines divide the staff into short sections called measures or bars. A double bar line, either heavy or light, is used to mark the ends of larger sections of music, including the very end of a piece, which is marked by a heavy double bar.

Figure 1.1. The Staff

Many different kinds of symbols can appear on, above, and below the staff. The notes and rests are the actual written music. A note stands for a sound; a rest stands for a silence. Other symbols on the staff, like the clef symbol, the key signature, and the time signature, tell you important information about the notes and measures. Symbols that appear above and below the music may tell you how fast it goes (tempo markings), how loud it should be (dynamic markings), where to go next (repeats, for example) and even give directions for how to perform particular notes (accents, for example).

Figure 1.2. Other Symbols on the Staff

Groups of staves

Staves are read from left to right. Beginning at the top of the page, they are read one staff at a time unless they are connected. If staves should be played at the same time (by the same person or by different people), they will be connected at least by a long vertical line at the left hand side. They may also be connected by their bar lines. Staves played by similar instruments or voices, or staves that should be played by the same person (for example, the right hand and left hand of a piano part) may be grouped together by braces or brackets at the beginning of each line.

Figure 1.3. Groups of Staves

Clef*

Treble Clef and Bass Clef

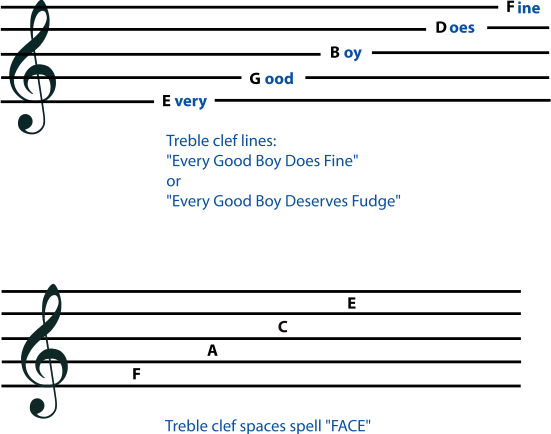

The first symbol that appears at the beginning of every music staff is a clef symbol. It is very important because it tells you which note (A, B, C, D, E, F, or G) is found on each line or space. For example, a treble clef symbol tells you that the second line from the bottom (the line that the symbol curls around) is "G". On any staff, the notes are always arranged so that the next letter is always on the next higher line or space. The last note letter, G, is always followed by another A.

Figure 1.4. Treble Clef

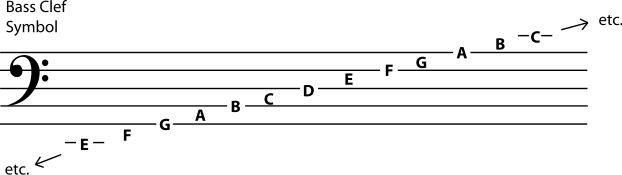

A bass clef symbol tells you that the second line from the top (the one bracketed by the symbol's dots) is F. The notes are still arranged in ascending order, but they are all in different places than they were in treble clef.

Figure 1.5. Bass Clef

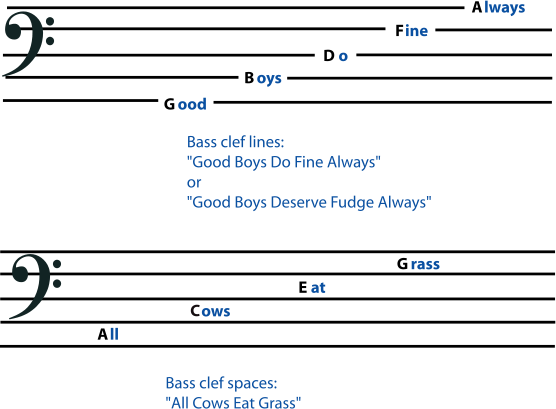

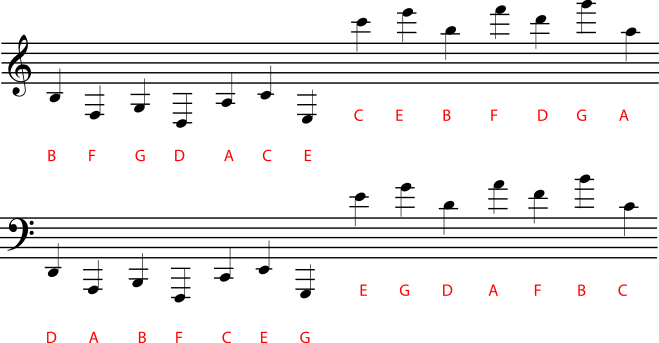

Memorizing the Notes in Bass and Treble Clef

One of the first steps in learning to read music in a particular clef is memorizing where the notes are. Many students prefer to memorize the notes and spaces separately. Here are some of the most popular mnemonics used.

Figure 1.6.

Moveable Clefs

Most music these days is written in either bass clef or treble clef, but some music is written in a C clef. The C clef is moveable: whatever line it centers on is a middle C.

Figure 1.7. C Clefs

The bass and treble clefs were also once moveable, but it is now very rare to see them anywhere but in their standard positions. If you do see a treble or bass clef symbol in an unusual place, remember: treble clef is a G clef; its spiral curls around a G. Bass clef is an F clef; its two dots center around an F.

Figure 1.8. Moveable G and F Clefs

Much more common is the use of a treble clef that is meant to be read one octave below the written pitch. Since many people are uncomfortable reading bass clef, someone writing music that is meant to sound in the region of the bass clef may decide to write it in the treble clef so that it is easy to read. A very small "8" at the bottom of the treble clef symbol means that the notes should sound one octave lower than they are written.

Figure 1.9.

Why use different clefs?

Music is easier to read and write if most of the notes fall on the staff and few ledger lines have to be used.

Figure 1.10.

The G indicated by the treble clef is the G above middle C, while the F indicated by the bass clef is the F below middle C. (C clef indicates middle C.) So treble clef and bass clef together cover many of the notes that are in the range of human voices and of most instruments. Voices and instruments with higher ranges usually learn to read treble clef, while voices and instruments with lower ranges usually learn to read bass clef. Instruments with ranges that do not fall comfortably into either bass or treble clef may use a C clef or may be transposing instruments.

Figure 1.11.

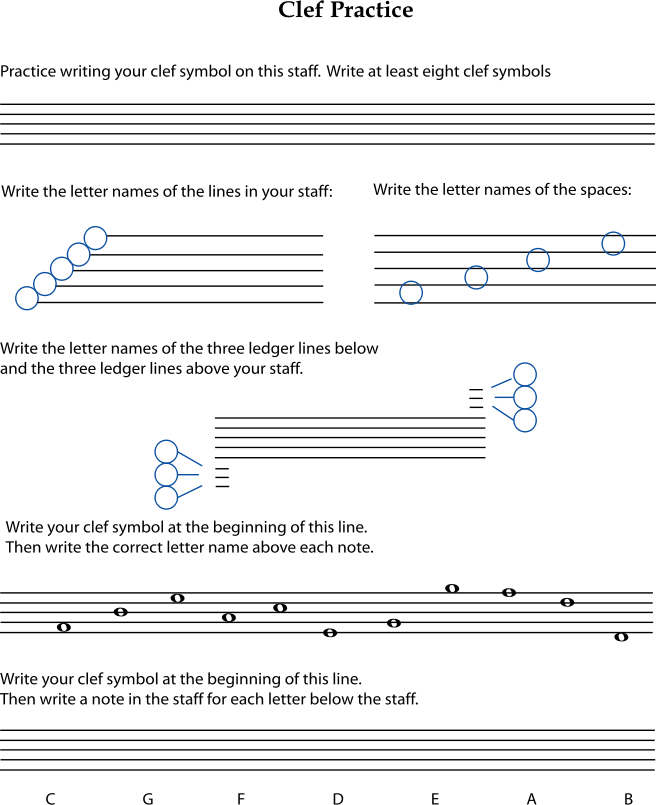

Exercise 1.2.2. (Go to Solution)

Choose a clef in which you need to practice recognizing notes above and below the staff in Figure 1.13. Write the clef sign at the beginning of the staff, and then write the correct note names below each note.

Figure 1.13.

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 1.2.2. (Return to Exercise)

Figure 1.16 shows the answers for treble and bass clef. If you have done another clef, have your teacher check your answers.

Figure 1.16.

Solution to Exercise 1.2.3. (Return to Exercise)

Figure 1.17 shows the answers for treble clef, and Figure 1.18 the answers for bass clef. If you are working in a more unusual clef, have your teacher check your answers.

Figure 1.17.

Figure 1.18.

Pitch: Sharp, Flat, and Natural Notes*

The pitch of a note is how high or low it sounds. Pitch depends on the frequency of the fundamental sound wave of the note. The higher the frequency of a sound wave, and the shorter its wavelength, the higher its pitch sounds. But musicians usually don't want to talk about wavelengths and frequencies. Instead, they just give the different pitches different letter names: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. These seven letters name all the natural notes (on a keyboard, that's all the white keys) within one octave. (When you get to the eighth natural note, you start the next octave on another A.)

Figure 1.19.

But in Western music there are twelve notes in each octave that are in common use. How do you name the other five notes (on a keyboard, the black keys)?

Figure 1.20.

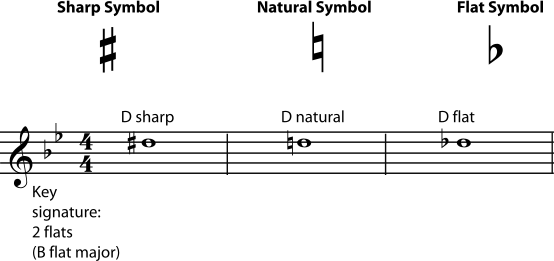

A sharp sign means "the note that is one half step higher than the natural note". A flat sign means "the note that is one half step lower than the natural note". Some of the natural notes are only one half step apart, but most of them are a whole step apart. When they are a whole step apart, the note in between them can only be named using a flat or a sharp.

Figure 1.21.

Notice that, using flats and sharps, any pitch can be given more than one note name. For example, the G sharp and the A flat are played on the same key on the keyboard; they sound the same. You can also name and write the F natural as "E sharp"; F natural is the note that is a half step higher than E natural, which is the definition of E sharp. Notes that have different names but sound the same are called enharmonic notes.

Figure 1.22.

Sharp and flat signs can be used in two ways: they can be part of a key signature, or they can mark accidentals. For example, if most of the C's in a piece of music are going to be sharp, then a sharp sign is put in the "C" space at the beginning of the staff, in the key signature. If only a few of the C's are going to be sharp, then those C's are marked individually with a sharp sign right in front of them. Pitches that are not in the key signature are called accidentals.

Figure 1.23.

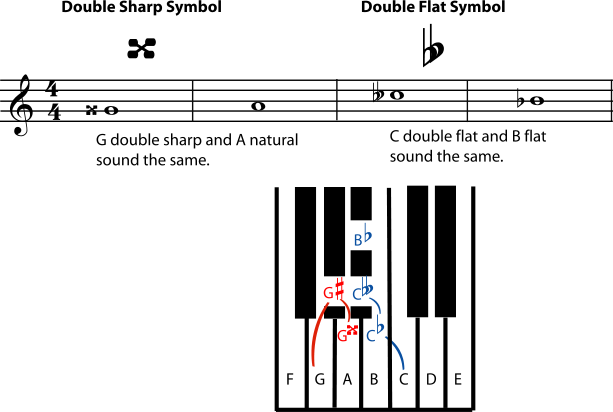

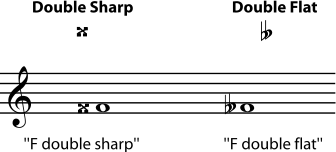

A note can also be double sharp or double flat. A double sharp is two half steps (one whole step) higher than the natural note; a double flat is two half steps (a whole step) lower. Triple, quadruple, etc. sharps and flats are rare, but follow the same pattern: every sharp or flat raises or lowers the pitch one more half step.

Using double or triple sharps or flats may seem to be making things more difficult than they need to be. Why not call the note "A natural" instead of "G double sharp"? The answer is that, although A natural and G double sharp are the same pitch, they don't have the same function within a particular chord or a particular key. For musicians who understand some music theory (and that includes most performers, not just composers and music teachers), calling a note "G double sharp" gives important and useful information about how that note functions in the chord and in the progression of the harmony.

Figure 1.24.

Key Signature*

Do key signatures make music more complicated than it needs to be? Is there an easier way? Join the discussion at Opening Measures.

The key signature comes right after the clef symbol on the staff. It may have either some sharp symbols on particular lines or spaces, or some flat symbols, again on particular lines or spaces. If there are no flats or sharps listed after the clef symbol, then the key signature is "all notes are natural".

In common notation, clef and key signature are the only symbols that normally appear on every staff. They appear so often because they are such important symbols; they tell you what note is on each line and space of the staff. The clef tells you the letter name of the note (A, B, C, etc.), and the key tells you whether the note is sharp, flat or natural.

Figure 1.25.

The key signature is a list of all the sharps and flats in the key that the music is in. When a sharp (or flat) appears on a line or space in the key signature, all the notes on that line or space are sharp (or flat), and all other notes with the same letter names in other octaves are also sharp (or flat).

Figure 1.26.

The sharps or flats always appear in the same order in all key signatures. This is the same order in which they are added as keys get sharper or flatter. For example, if a key (G major or E minor) has only one sharp, it will be F sharp, so F sharp is always the first sharp listed in a sharp key signature. The keys that have two sharps (D major and B minor) have F sharp and C sharp, so C sharp is always the second sharp in a key signature, and so on. The order of sharps is: F sharp, C sharp, G sharp, D sharp, A sharp, E sharp, B sharp. The order of flats is the reverse of the order of sharps: B flat, E flat, A flat, D flat, G flat, C flat, F flat. So the keys with only one flat (F major and D minor) have a B flat; the keys with two flats (B flat major and G minor) have B flat and E flat; and so on. The order of flats and sharps, like the order of the keys themselves, follows a circle of fifths.

Figure 1.27.

If you do not know the name of the key of a piece of music, the key signature can help you find out. Assume for a moment that you are in a major key. If the key contains sharps, the name of the key is one half step higher than the last sharp in the key signature. If the key contains flats, the name of the key signature is the name of the second-to-last flat in the key signature.

Example 1.1.

Figure 1.28 demonstrates quick ways to name the (major) key simply by looking at the key signature. In flat keys, the second-to-last flat names the key. In sharp keys, the note that names the key is one half step above the final sharp.

Figure 1.28.

The only major keys that these rules do not work for are C major (no flats or sharps) and F major (one flat). It is easiest just to memorize the key signatures for these two very common keys. If you want a rule that also works for the key of F major, remember that the second-to-last flat is always a perfect fourth higher than (or a perfect fifth lower than) the final flat. So you can also say that the name of the key signature is a perfect fourth lower than the name of the final flat.

Figure 1.29.

If the music is in a minor key, it will be in the relative minor of the major key for that key signature. You may be able to tell just from listening (see Major Keys and Scales) whether the music is in a major or minor key. If not, the best clue is to look at the final chord. That chord (and often the final note of the melody, also) will usually name the key.

Exercise 1.4.1. (Go to Solution)

Write the key signatures asked for in Figure 1.30 and name the major keys that they represent.

Figure 1.30.

Solutions to Exercises

Enharmonic Spelling*

Enharmonic Notes

In common notation, any note can be sharp, flat, or natural. A sharp symbol raises the pitch (of a natural note) by one half step; a flat symbol lowers it by one half step.

Figure 1.32.

Why do we bother with these symbols? There are twelve pitches available within any octave. We could give each of those twelve pitches its own name (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, and L) and its own line or space on a staff. But that would actually be fairly inefficient, because most music is in a particular key. And music that is in a major or minor key will tend to use only seven of those twelve notes. So music is easier to read if it has only lines, spaces, and notes for the seven pitches it is (mostly) going to use, plus a way to write the occasional notes that are not in the key.

This is basically what common notation does. There are only seven note names (A, B, C, D, E, F, G), and each line or space on a staff will correspond with one of those note names. To get all twelve pitches using only the seven note names, we allow any of these notes to be sharp, flat, or natural. Look at the notes on a keyboard.

Because most of the natural notes are two half steps apart, there are plenty of pitches that you can only get by naming them with either a flat or a sharp (on the keyboard, the "black key" notes). For example, the note in between D natural and E natural can be named either D sharp or E flat. These two names look very different on the staff, but they are going to sound exactly the same, since you play both of them by pressing the same black key on the piano.

Figure 1.34.

This is an example of enharmonic spelling. Two notes are enharmonic if they sound the same on a piano but are named and written differently.

Exercise 1.5.1. (Go to Solution)

Name the other enharmonic notes that are listed above the black keys on the keyboard in Figure 1.33. Write them on a treble clef staff.

But these are not the only possible enharmonic notes. Any note can be flat or sharp, so you can have, for example, an E sharp. Looking at the keyboard and remembering that the definition of sharp is "one half step higher than natural", you can see that an E sharp must sound the same as an F natural. Why would you choose to call the note E sharp instead of F natural? Even though they sound the same, E sharp and F natural, as they are actually used in music, are different notes. (They may, in some circumstances, also sound different; see below.) Not only will they look different when written on a staff, but they will have different functions within a key and different relationships with the other notes of a piece of music. So a composer may very well prefer to write an E sharp, because that makes the note's place in the harmonies of a piece more clear to the performer. (Please see Triads, Beyond Triads, and Harmonic Analysis for more on how individual notes fit into chords and harmonic progressions.)

In fact, this need (to make each note's place in the harmony very clear) is so important that double sharps and double flats have been invented to help do it. A double sharp is two half steps (one whole step) higher than the natural note. A double flat is two half steps lower than the natural note. Double sharps and flats are fairly rare, and triple and quadruple flats even rarer, but all are allowed.

Figure 1.35.

Exercise 1.5.2. (Go to Solution)

Give at least one enharmonic spelling for the following notes. Try to give more than one. (Look at the keyboard again if you need to.)

-

E natural

-

B natural

-

C natural

-

G natural

-

A natural

Enharmonic Keys and Scales

Keys and scales can also be enharmonic. Major keys, for example, always follow the same pattern of half steps and whole steps. (See Major Keys and Scales. Minor keys also all follow the same pattern, different from the major scale pattern; see Minor Keys.) So whether you start a major scale on an E flat, or start it on a D sharp, you will be following the same pattern, playing the same piano keys as you go up the scale. But the notes of the two scales will have different names, the scales will look very different when written, and musicians may think of them as being different. For example, most instrumentalists would find it easier to play in E flat than in D sharp. In some cases, an E flat major scale may even sound slightly different from a D sharp major scale. (See below.)

Figure 1.36.

Since the scales are the same, D sharp major and E flat major are also enharmonic keys. Again, their key signatures will look very different, but music in D sharp will not be any higher or lower than music in E flat.

Figure 1.37. Enharmonic Keys

Exercise 1.5.3. (Go to Solution)

Give an enharmonic name and key signature for the keys given in Figure 1.38. (If you are not well-versed in key signatures yet, pick the easiest enharmonic spelling for the key name, and the easiest enharmonic spelling for every note in the key signature. Writing out the scales may help, too.)

Figure 1.38.

Enharmonic Intervals and Chords

Figure 1.39.

Chords and intervals also can have enharmonic spellings. Again, it is important to name a chord or interval as it has been spelled, in order to understand how it fits into the rest of the music. A C sharp major chord means something different in the key of D than a D flat major chord does. And an interval of a diminished fourth means something different than an interval of a major third, even though they would be played using the same keys on a piano. (For practice naming intervals, see Interval. For practice naming chords, see Naming Triads and Beyond Triads. For an introduction to how chords function in a harmony, see Beginning Harmonic Analysis.)

Figure 1.40.

Enharmonic Spellings and Equal Temperament

All of the above discussion assumes that all notes are tuned in equal temperament. Equal temperament has become the "official" tuning system for Western music. It is easy to use in pianos and other instruments that are difficult to retune (organ, harp, and xylophone, to name just a few), precisely because enharmonic notes sound exactly the same. But voices and instruments that can fine-tune quickly (for example violins, clarinets, and trombones) often move away from equal temperament. They sometimes drift, consciously or unconsciously, towards just intonation, which is more closely based on the harmonic series. When this happens, enharmonically spelled notes, scales, intervals, and chords, may not only be theoretically different. They may also actually be slightly different pitches. The differences between, say, a D sharp and an E flat, when this happens, are very small, but may be large enough to be noticeable. Many Non-western music traditions also do not use equal temperament. Sharps and flats used to notate music in these traditions should not be assumed to mean a change in pitch equal to an equal-temperament half-step. For definitions and discussions of equal temperament, just intonation, and other tuning systems, please see Tuning Systems.

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 1.5.1. (Return to Exercise)

-

C sharp and D flat

-

F sharp and G flat

-

G sharp and A flat

-

A sharp and B flat

Figure 1.41.

Solution to Exercise 1.5.2. (Return to Exercise)

-

F flat; D double sharp

-

C flat; A double sharp

-

B sharp; D double flat

-

F double sharp; A double flat

-

G double sharp; B double flat