1.3. Style

Dynamics and Accents*

Dynamics

Sounds, including music, can be barely audible, or loud enough to hurt your ears, or anywhere in between. When they want to talk about the loudness of a sound, scientists and engineers talk about amplitude. Musicians talk about dynamics. The amplitude of a sound is a particular number, usually measured in decibels, but dynamics are relative; an orchestra playing fortissimo sounds much louder than a single violin playing fortissimo. The exact interpretation of each dynamic marking in a piece of music depends on:

-

comparison with other dynamics in that piece

-

the typical dynamic range for that instrument or ensemble

-

the abilities of the performer(s)

-

the traditions of the musical genre being performed

-

the acoustics of the performance space

Traditionally, dynamic markings are based on Italian words, although there is nothing wrong with simply writing things like "quietly" or "louder" in the music. Forte means loud and piano means quiet. The instrument commonly called the "piano" by the way, was originally called a "pianoforte" because it could play dynamics, unlike earlier popular keyboard instruments like the harpsichord and spinet.

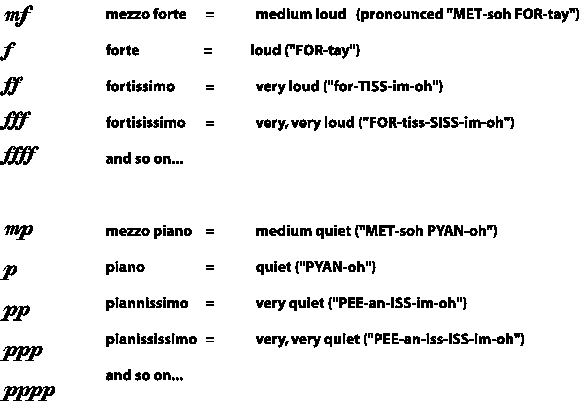

Figure 1.89. Typical Dynamic Markings

When a composer writes a forte into a part, followed by a piano, the intent is for the music to be loud, and then suddenly quiet. If the composer wants the change from one dynamic level to another to be gradual, different markings are added. A crescendo (pronounced "cresh-EN-doe") means "gradually get louder"; a decrescendo or diminuendo means "gradually get quieter".

Figure 1.90. Gradual Dynamic Markings

Accents

A composer may want a particular note to be louder than all the rest, or may want the very beginning of a note to be loudest. Accents are markings that are used to indicate these especially-strong-sounding notes. There are a few different types of written accents (see Figure 1.91), but, like dynamics, the proper way to perform a given accent also depends on the instrument playing it, as well as the style and period of the music. Some accents may even be played by making the note longer or shorter than the other notes, in addition to, or even instead of being, louder. (See articulation for more about accents.)

Figure 1.91. Common Accents

Articulation*

What is Articulation?

The word articulation generally refers to how the pieces of something are joined together; for example, how bones are connected to make a skeleton or syllables are connected to make a word. Articulation depends on what is happening at the beginning and end of each segment, as well as in between the segments.

In music, the segments are the individual notes of a line in the music. This could be the melodic line, the bass line, or a part of the harmony. The line might be performed by any musician or group of musicians: a singer, for example, or a bassoonist, a violin section, or a trumpet and saxophone together. In any case, it is a string of notes that follow one after the other and that belong together in the music.The articulation is what happens in between the notes. The attack - the beginning of a note - and the amount of space in between the notes are particularly important.

Performing Articulations

Descriptions of how each articulation is done cannot be given here, because they depend too much on the particular instrument that is making the music. In other words, the technique that a violin player uses to slur notes will be completely different from the technique used by a trumpet player, and a pianist and a vocalist will do different things to make a melody sound legato. In fact, the violinist will have some articulations available (such as pizzicato, or "plucked") that a trumpet player will never see.

So if you are wondering how to play slurs on your guitar or staccato on your clarinet, ask your music teacher or director. What you will find here is a short list of the most common articulations: their names, what they look like when notated, and a vague description of how they sound. The descriptions have to be vague, because articulation, besides depending on the instrument, also depends on the style of the music. Exactly how much space there should be between staccato eighth notes, for example, depends on tempo as well as on whether you're playing Rossini or Sousa. To give you some idea of the difference that articulation makes, though, here are audio examples of a violin playing a legato and a staccato passage. (For more audio examples of violin articulations, please see Common Violin Terminology.)

Common Articulations

Staccato notes are short, with plenty of space between them. Please note that this doesn't mean that the tempo or rhythm goes any faster. The tempo and rhythm are not affected by articulations; the staccato notes sound shorter than written only because of the extra space between them.

Figure 1.92. Staccato

Legato is the opposite of staccato. The notes are very connected; there is no space between the notes at all. There is, however, still some sort of articulation that causes a slight but definite break between the notes (for example, the violin player's bow changes direction, the guitar player plucks the string again, or the wind player uses the tongue to interrupt the stream of air).

Figure 1.93. Legato

Accents - An accent requires that a note stand out more than the unaccented notes around it. Accents are usually performed by making the accented note, or the beginning of the accented note, louder than the rest of the music. Although this is mostly a quick change in dynamics, it usually affects the articulation of the note, too. The extra loudness of the note often requires a stronger, more definite attack at the beginning of the accented note, and it is emphasized by putting some space before and after the accented notes. The effect of a lot of accented notes in a row may sound marcato.

Figure 1.94. Accents

A slur is marked by a curved line joining any number of notes. When notes are slurred, only the first note under each slur marking has a definite articulation at the beginning. The rest of the notes are so seamlessly connected that there is no break between the notes. A good example of slurring occurs when a vocalist sings more than one note on the same syllable of text.

Figure 1.95. Slurs

A tie looks like a slur, but it is between two notes that are the same pitch. A tie is not really an articulation marking. It is included here because it looks like one, which can cause confusion for beginners. When notes are tied together, they are played as if they are one single note that is the length of all the notes that are tied together. (Please see Dots, Ties, and Borrowed Divisions.)

Figure 1.96. Slurs vs. Ties

A portamento is a smooth glide between the two notes, including all the pitches in between. For some instruments, like violin and trombone, this includes even the pitches in between the written notes. For other instruments, such as guitar, it means sliding through all of the possible notes between the two written pitches.

Figure 1.97. Portamento

Although unusual in traditional common notation, a type of portamento that includes only one written pitch can be found in some styles of music, notably jazz, blues, and rock. As the notation suggests, the proper performance of scoops and fall-offs requires that the portamento begins (in scoops) or ends (in fall-offs) with the slide itself, rather than with a specific note.

Figure 1.98. Scoops and Fall-offs

Some articulations may be some combination of staccato, legato, and accent. Marcato, for example means "marked" in the sense of "stressed" or "noticeable". Notes marked marcato have enough of an accent and/or enough space between them to make each note seem stressed or set apart. They are usually longer than staccato but shorter than legato. Other notes may be marked with a combination of articulation symbols, for example legato with accents. As always, the best way to perform such notes depends on the instrument and the style of the music.

Figure 1.99. Some Possible Combination Markings

Plenty of music has no articulation marks at all, or marks on only a few notes. Often, such music calls for notes that are a little more separate or defined than legato, but still nowhere as short as staccato. Mostly, though, it is up to the performer to know what is considered proper for a particular piece. For example, most ballads are sung legato, and most marches are played fairly staccato or marcato, whether they are marked that way or not. Furthermore, singing or playing a phrase with musicianship often requires knowing which notes of the phrase should be legato, which should be more separate, where to add a little portamento, and so on. This does not mean the best players consciously decide how to play each note. Good articulation comes naturally to the musician who has mastered the instrument and the style of the music.